For the avoidance of doubt, as lawyers like to say,

companies can eliminate their corporate travel emissions in only one way, and

that’s not to travel.

Yet, though that has happened during the coronavirus

pandemic, business trips are not about to cease permanently. Even a slew of

professional service firms which have made public net zero emission pledges in

recent months have committed to reduce their travel-related emissions by,

typically, 30 percent to 35 percent from 2019 levels—certainly not 100 percent.

But once companies have cut emissions by cutting their

demand, is there any point in going on to address supply as well? Can a

company’s choice of, and engagement with, travel suppliers contribute in any

meaningful way to tackling the climate crisis?

There is even an argument that a few token environmental

questions in a request for proposal deflects companies’ responsibility for

reducing their travel-generated pollution from themselves to their suppliers.

In that case, is attempting to green the supply chain futile at best,

counter-productive at worst?

Absolutely not, according to those in travel who have

engaged deeply with sustainability issues. “Managing demand is more important

than managing suppliers but yes, it is still worthwhile,” said Daniel Tallos,

travel buyer for a large retail industry company.

Supplier engagement makes total sense for two key reasons,

Tallos and other travel managers and sustainability experts maintain. The first

is that some supplier choices genuinely are less polluting than others. The

second, perhaps overlooked, reason is that corporate customer pressure forces

suppliers to go greener.

However, pressure of this kind is likely to succeed only if

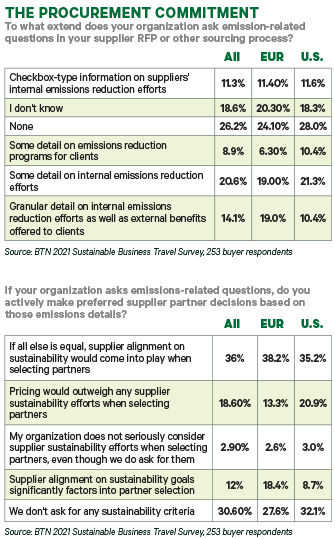

suppliers detect sincerity from their customers. BTN’s survey of travel buyers

conducted for this special issue, suggests attitudes vary widely. While 14

percent ask travel suppliers for granular detail about emissions reduction, and

another 30 percent for “some detail”, 11 percent characterize their requests as

no more than “checkbox-type” information requests and 26 percent say there is

no engagement with suppliers on sustainability at all. Nearly a fifth of travel

buyers don’t know.

Then there is the question of what action clients take on

the information they receive: 31 percent deploy no sustainability criteria in

their supplier decision-making and 3 percent admit to not seriously considering

the answers they do receive. Another 19 percent say pricing outweighs

suppliers’ sustainability records, while 36 percent say environmental factors

are influential only if all other decision factors are equal.

However, 12 percent of buyers are doing things differently.

They say supplier alignment on sustainability goals significantly factors into

partner selection.

To make that difference, said Andrew Perolls, CEO of

sustainable travel consultancy Greengage, “buying decisions need to balance

convenience, cost and CO2.” But companies need to show real intent to convert

this neatly alliterative slogan into practice. For Julia Fidler, senior sustainability

program manager for procurement at Microsoft, that means upending traditional

procurement practice and operating a double bottom line: one for financial

performance and a second for environmental impact.

“We’ve delivered a signal by sharing that we’re willing to

pay extra for sustainable fuel,” said Fidler. “Our ability to say we have

looked at this beyond the normal procurement perspective has had a ripple

effect. The interest from our peers and suppliers has been fantastic.”

Making Lower-Carbon Buying Choices

“Before choosing between two airlines, we have to think: ‘do

we need to travel?’” said Horst Bayer, founder of TravelHorst Sustainable

Business Travel Consulting. “If we decide it is necessary to travel, then yes,

we should look at whether one is more environmentally friendly than another.”

Factors which inform this determination are complex. They

include aircraft type, engine choice, load factor, fuel selection, route and

altitude flown. According to Cait Hewitt, deputy director of the UK-based

Aviation Environment Foundation, which campaigns on the impact of aviation on

people and the environment, the differences can be huge. “The work most helpful

to us is done by The International Council on Clean Transportation, which

suggests there can be a difference of 60 percent on a transatlantic flight from

one airline to another,” she says.

Perolls cites evaluations by business travel carbon

reporting consultancy Susterra of flight options to Glasgow from London’s five

airports. If customers choose London City Airport, CO2 emissions per kilometer

can be 43 percent higher than from Gatwick because of the steepness of the

climb on take-off and smaller aircraft types used.

However, obtaining reliable data for buyers to favor

airlines which pollute less is difficult; and putting that information in front

of travelers is even harder. Lack of data is the story asserted most

consistently and with most frustration by every interviewee for this article.

“It’s worth trying to do but it’s not information that’s easy to get at time of

booking,” said Hewitt. “It doesn’t seem possible to enter ‘most fuel-efficient

airline’ as a search criterion. You might get an airline’s average efficiency

but it’s harder on a route basis.”

Lack of visibility is also the most critical challenge

identified by Mark Avery, global business services and travel leader for PWC.

The firm’s UK travelers reduced travel-related CO2 emissions by 6 percent

between 2007 and 2019 in spite of the business more than doubling in size over

that period, but Avery feels he could achieve even more with good data.

“One of the challenges with where we are now is how do we

help our people make environmentally friendly decisions?” Avery said. “We don’t

provide anything at point of sale to help travelers. First, we need to ask ‘do

you need to travel?’ but then it doesn’t say ‘these are your choices and their

differentiation in terms of sustainability.’ I think we could get 10 [percent]

to 20 percent carbon reductions just by getting the right data to share with

the traveler at point of sale.

“Right now there is no discriminatory buying because of that

lack of point-of-sale discrimination. The only way we can move the dial is if

we can do that.”

Tallos feels exactly the same pain. “Our travelers are coming

to us asking how they can do the right thing,” he said. “We’re not in the right

place to help them at point of purchase to make the right decision. We can’t

message what is a wiser choice.”

Pressurizing Suppliers to Go Greener

Avery finds that “getting emissions data from airlines is a

challenge.” He presses them for average emissions per passenger per route but

it is rarely forthcoming.

Hewitt encourages buyers to keep pestering. “There is almost

an immediate response from carriers that it’s too complicated,” she said, “but

it would be helpful if travel managers put pressure on airlines to give them

the data to make better decisions. It applies pressure on them to upgrade their

fleets earlier than they would do purely for financial reasons.”

That’s only one way in which corporate customers can

influence their suppliers. Hewitt believes clients should set out the

environmental standards they expect of suppliers, for example by urging

airlines not to resist being included in global net zero commitments.

Customer pressure also exerts a subtler kind of influence,

which is on internal politics within suppliers. “Making connection with

sustainability teams at suppliers is vital,” said Microsoft’s Fidler. “It’s

almost giving a green light to those teams to go further with their initiatives

if they have clients who say ‘this is important.’”

Avery is seeing the influence begin to tell. “We give

suppliers feedback on how they compare environmentally to their peers,” he

said. “We invite them to speak to our sustainability people about why they have

been scored in that way. You can tell how interested they are by their

response. We’ve seen the quality of responses improve: We now have

sustainability people completing the surveys, not salespeople.”

Supplier engagement on sustainability has the potential to

go even deeper than that. One of the most striking examples is the declaration

Microsoft made in October 2019 on paying a premium for sustainable aviation

fuels equating to the total volume used on all flights undertaken by its

employees on flights between the U.S. and Netherlands with KLM and Delta Air

Lines. Microsoft and KLM have also committed jointly to other sustainable

travel initiatives.

For Fidler, the priority remains avoiding travel where not

required, but, she said, that’s not enough. “The elephant in the room is that

aircraft are still taking off even if your company’s not on them,” she said.

That’s why, in her view, a modern approach to sustainability is to work with

suppliers to be less polluting, not to shun them. Helping to finance a

transition to biofuels is one example of what Fidler calls, “supporting early

innovation”.

But how much influence can any single corporate client exert

on its own? Tallos wants to see buyers working together, especially through

industry associations. “Pressing suppliers to go greener is an impossible quest

unless customers take collective action,” he said. “Suppliers’ relative

dependence on a single customer is marginal, thus their relative willingness to

listen to is also very limited.”

Choice of Transport Mode Outweighs Choice of Supplier

However one cuts its, until the means by which aircraft are

propelled change radically, greening the supply chain can only go so far when

that supplier is an airline. “It’s worth trying, although switching to rail

will nearly always give you a better outcome,” said Hewitt. “I’ve never seen

evidence of a route that is more efficient by plane. Generally, emissions are

reduced 90 percent when travelling by rail rather than air.”

To return to Susterra’s London-Glasgow example, making the

journey by train causes emissions of 0.05kg of CO2 per kilometre compared with

0.23kg when flying from Gatwick or 0.33kg when flying from London City, and

that’s even before number of passengers (much greater on a train) is taken into

account.

But Western Europe, China and Japan are perhaps the only

places where rail is a consistent alternative to air, and even then only for

journeys of a few hours. On most routes, if travel is deemed necessary, a more

sophisticated approach to supplier management remains the only means of

reducing environmental impact.

Hotels: A Tricky Category for Sustainable Procurement

If data opacity makes sustainable procurement hard enough

for the airline category, double that and add a nought on the end for

accommodation. “Hotels are far more complex than transportation,” said

Microsoft’s Julia Fidler. Making like-for-like comparisons between suppliers is

fraught with difficulty. For example, newer hotels are more energy-efficient but

weighed against that is the energy required to build a new property when

established alternatives exist.

As a result, said Fidler, “I certainly don’t know any single

accreditation you can apply globally and that you could ask hotels to work

towards.”

Nevertheless, Microsoft makes what efforts it can. It shares

hotels’ sustainability initiatives with travelers and carries out environmental

reviews at chain level. Perhaps most importantly in the short term, Microsoft

is trying to fix the data problem by asking hotel suppliers to commit to the

Carbon Disclosure Project, whose mission is to persuade suppliers to provide

data and set science-based emissions reduction targets.

Daniel Tallos is another buyer stymied by lack of

standardization but trying to effect change, for example by including the

Global Business Travel Association’s standard questions on sustainability in

his company’s most recent hotel RFP. “We are moving towards a point where, if

they don’t answer our questions in a meaningful manner, we won’t work with

them,” Tallos said.