Scott Gillespie is founder and CEO of travel management consultancy tClara.

Scott Gillespie is founder and CEO of travel management consultancy tClara.

“If we can save 10 percent on travel, we can take 10 percent more trips!”

So said my client, a travel category leader, as she explained her motivation for managing down the cost of travel. This was in 1994. She understood procurement’s central goal, one that has been the basis for managing travel for the last three decades.

Most of today’s managed travel principles exist because they serve this goal so well. We control the spend, prioritize savings, design policies and tools to shift volume to preferred suppliers, and strive to purchase low-cost trips—all in order to keep prices low and take more trips.

After 30 years, it’s fair to ask if this strategy is still warranted. For many companies, I say it is not.

In February 2022 tClara asked 522 U.S.-based business leaders to rank seven travel-related goals. Their top five priorities:

- More successful trips

- Protecting the health and safety of their travelers

- Increasing road warrior retention

- Reducing travel-related carbon emissions, and

- Reducing the number of business trips.

The two lowest priorities? Reducing the cost of business trips and increasing the number of business trips.

Notably, not one of the “lower prices, more trips” principles help to achieve any of the top five goals listed above. Holy crap—we need a new strategy for managing travel.

The “Less Travel, Better Results” Strategy

Goals require strategies, so we need a set of cohesive principles to achieve these new goals. The “less travel, better results” strategy does so in no small part by ignoring the quest for low prices and cost savings. It works by using four principles.

1. Travel Less, but Travel Better

Research underway at tClara indicates that 25 percent to 30 percent of U.S.-based business trips have low value. I suspect the same is true for trips based in the U.K. and Europe. These are the trips that should be eliminated, as we don’t want to eliminate moderate- and high-value trips.

The key to this principle is to embrace higher travel prices. Radical, yes, but remarkably effective. Why?

- Higher prices eliminate demand for low-value trips, as these will be harder to justify.

- Higher prices chew up a travel budget faster, so fewer trips will be taken. Note goal No. 5 above, in tClara's survey.

- Higher prices mean higher profit margins for travel suppliers. This could make it easier for travel suppliers (or buyers; see below) to decarbonize travel. See goal No. 4 above.

- Higher prices can—and should—be used to buy higher-quality travel. Research links higher-quality travel to more trip success, better traveler health and well-being, and better retention. See goals No. 1, 2 and 3 above.

Intentionally paying higher prices is a big ask of most managers. They’ll need to be persuaded of these merits and to be more diligent about denying requests for low-value trips. The upside? It preserves their travel budgets for the more justified higher-value trips.

2. Pay More to Pollute Less

The two most important metrics of a travel program’s emissions are its total emissions and its carbon intensity. One measure of carbon intensity can be derived by dividing total emissions by the travel spend. Companies should calculate their carbon intensity for their baseline year (e.g., one kilogram per dollar, euro or pound sterling in 2019). Now, strive to reduce this metric every year. Here’s how:

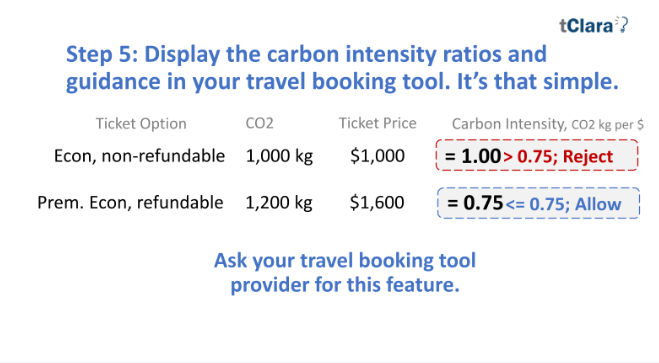

Imagine a company setting a goal to reduce its carbon intensity by 25 percent (e.g., down to 0.75 kilograms of CO2 per dollar, euro or pound sterling). With a bit of innovation by its corporate booking tool, the company could now prioritize flight itineraries that have acceptably low carbon intensities.

Credit: tClara/Scott Gillespie

Credit: tClara/Scott Gillespie

Here’s a simple example: Assume a company has $12,000 to spend on air travel, and it can buy 12 economy tickets at $1,000 each, or buy three business-class tickets at $4,000 each. Let's say the economy seats each have 1,000 kilograms of CO2 emissions, and the business-class seats each have 3,000 kilograms. (A common rule of thumb is that a berth in business class is three times as carbon emitting as a seat in economy.) The carbon intensity of the economy seat is 1.0, and for the business class seat it is 0.75.

It's better for the climate if the $12,000 budget is used on the three business class seats, as they will produce 25 percent fewer emissions than if the company flew 12 people in economy class: 9,000 kilograms vs. 12,000 kilograms. It's not even close when the business-class fare is at least four times the economy ticket.

But if the business-class fare is $2,000 each, its carbon intensity goes to 2.0 CO2 kilograms per dollar. This makes flying in economy better for this budget. Why? Because using the budget on six business-class tickets would emit 18,000 kilograms of CO2, or 50 percent more than the "all in economy" budget generates.

It's the carbon intensity, not the cabin, that matters to the climate. The lower the intensity, the better. Fair warning—cheap tickets in economy do poorly on this test, while more expensive and typically higher-quality itineraries do well. Use this carbon intensity cap to justify paying more while polluting less.

The critical question here is how to balance the desired reduction in carbon intensity with the resulting higher prices and fewer trips afforded by the budget. In the example above, it’s worth pointing out that using the budget on three business-class tickets would result in a 75 percent reduction of business trips, if the travel budget remained unchanged. If fewer trips are taken, surely the least-valuable ones will be eliminated first. But at what point are high-value trips put at risk?

Companies will have to decide for themselves what carbon intensity cap would be right for their programs. While that question is beyond the scope of this article, getting the right answer requires a company to more carefully evaluate the merits of each business trip. tClara will publish research on this in the near future.

3. Measure Before and After

Management’s top priority is achieving more successful trip outcomes. So let’s agree that we need to start measuring trip success. The key is conducting simple pre- and post-trip assessments.

Ask “What are your goals for this trip?” before the trip, and afterward ask “How successful was this trip?” Fortunately, 90 percent of the business leaders surveyed by tClara supported requiring this of their travelers.

If management really cares about traveler health and safety, then we need to measure that, too. Ditto for road warrior retention and travel’s decarbonization.

None of these goal-driven metrics are hard to produce at scale. Travel management companies should be driving the development of these metrics and helping their clients to interpret the results. It’s an important new frontier for adding value.

4. Trade Savings for Success

If higher prices are better (and they are for this strategy), then discounts and savings are counter-productive. Now imagine what a creative procurement pro could get from suppliers in return for buying higher-quality travel and foregoing the customary discounts.

Surely such a buyer would leapfrog to the front of the “most valued customer” line. Suppliers would likely bend over backward to give this buyer and their travelers excellent service and last-minute availability. The buyer’s travelers would quickly climb the loyalty ladder rungs, which in turn yields better service and loyalty rewards.

Buyers who play the “no discount” card right will find new sources of value while making progress toward all of management’s top travel-related goals. Procurement heads must be spinning.

Unlock Travel’s Strategic Value

The key to increasing travel’s strategic value requires four bold and thoughtful actions. Use the pre-trip assessment to tie each business trip to the business goal that it most directly supports. Buy itineraries that are under the carbon intensity cap. Prefer those suppliers who enable successful outcomes. Then use the trip’s cost and the post-trip success rating to illuminate the value of traveling for each goal.

The “less travel, better results” strategy is designed to achieve goals that matter today. Perhaps it will endure for the next 30 years.